On Friday, October 7th, students celebrated the start of Family Weekend with a joyous workday on the Old Acre. On what may well have been the last hot and sunny day of the season, students and their family members harvested tomatoes, peppers, kale, and collard greens. Students washed and packed the greens, then pulled out the end-of-season kale and collard green plants from the field. Participants then chopped the plants into small pieces and composted them, before rolling up the tarps and tidying up the now-empty beds, ready for the upcoming planting of cover crop. Students also raked beds, sowed wheat, weeded the upper berm area, and continued the weekly task of stringing marigold garlands.

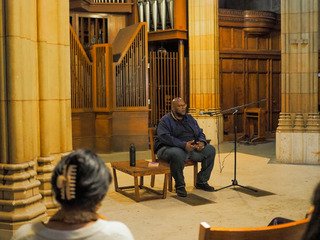

As the workday portion of the afternoon concluded, participants gathered in the Lazarus Pavilion for cool, refreshing apple cider and a plethora of delicious and creative pizzas. Carmen Ortega ’24, a 2022 Yale Farm Summer Intern, shared her knead 2 know on indigenous farming practices in New Mexico. Ortega is from Albuquerque and identifies as mestiza, meaning she has both Spanish and Indigenous roots. Ortega talked about food and cooking as a form of both cultural and physical survival; she discussed the topography and climate of New Mexico, some of the highest and driest in the country, and how farmers utilize various techniques to get plants to thrive in this arid region. She described many practices used to combat water scarcity such as canal irrigation and rainwater collection. Ortega also discussed the traditional practice of co-planting the “Three Sisters,” corn, beans, and squash. Additionally, Ortega presented elements of spirituality and worship as they relate to water and agriculture in indigenous cultures. Ortega talked about how some Southwestern Native Americans have lost agricultural knowledge through forced acculturation, and about efforts to reconnect people to the land, which her research also aims to do.

After the k2k, students and parents lingered in the Lazarus Pavilion, listening to music as the Culinary Events Team continued to churn out pies.

Thank you to everyone who came out to the Farm this weekend. It was so wonderful to meet your families and share the YSFP love. Photos from the k2k and workday can be viewed here.