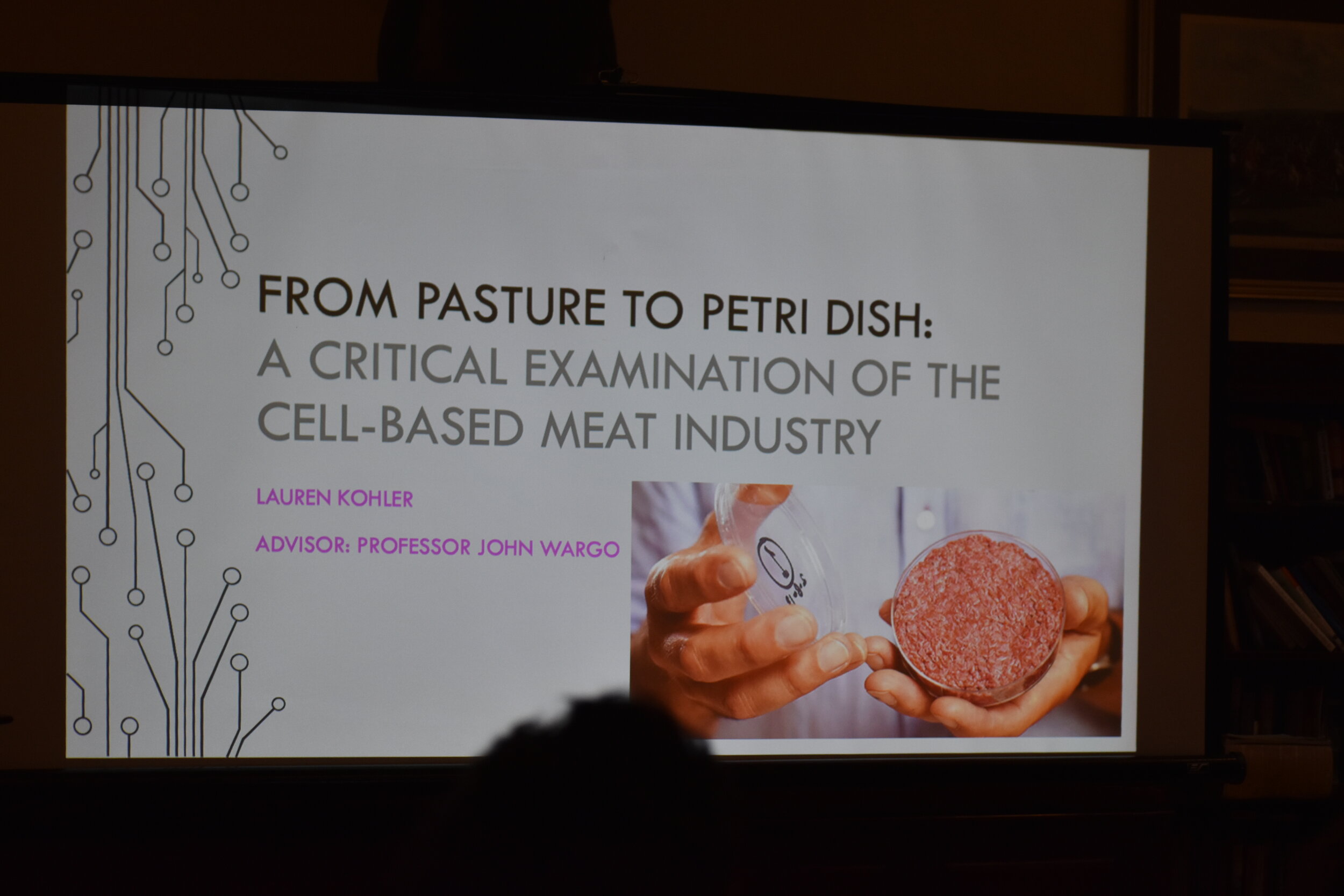

Lauren Kohler ’19 did just about everything there is to do at the YSFP, from tending Yale Farm crops to writing our ever-popular newsletter. The former Farm Manager is no longer harvesting carrots on the Old Acre, but she’s not done thinking about the food we eat and where it comes from. Kohler is now the Director of Food Systems Philanthropy at Stray Dog Institute, a private operating foundation that provides funding to and conducts research with organizations in the food systems and farmed animal advocacy movements. YSFP communications team member Sadie Bograd ’25 spoke with Kohler about her work and how it was shaped by her time at the Yale Farm.

This conversation is part of a new Voices series about the exciting work YSFP alumni are doing in the world of food and agriculture. The transcript has been edited lightly for length and clarity.

How would you describe your work at Stray Dog Institute?

I help execute, develop, and manage our food systems programming, philanthropy, and strategy. In addition to managing our grants, I provide support beyond the check: for example, sharing a funder perspective on a presentation, or weighing in on a new strategy. I've also facilitated three different working groups since I came onto the team [in 2019], helping to provide a space for collaboration and a facilitating force for organizations in the movement. My work spans the philanthropic side and the connector, facilitator, and collaborative space-builder role.

On that note, could you describe the general landscape of food systems grant-making and the food systems movement?

Stray Dog Institute sits at the intersection of the farmed animal advocacy and food system transformation movements. Our benefactors, Chuck and Jennifer [Laue], have dedicated their time and their money to trying to end factory farming and make the world better for people, animals, and the planet. Because of their vision, we keep animals at the center of our work, and that's why we're focused on ending factory farming specifically. But we also recognize that factory farming exists within the broader landscape of the food system. And you can't look at industrial animal agriculture without looking at the intersecting oppressions and injustices that create the extractive, exploitative food system that we have today. We find a lot of overlap with [food systems] groups that are fighting to end factory farming in the US. It may not be for animals: it may be for rural communities, environmental justice reasons, public health reasons, soil health reasons.

Do all those different groups usually work together? And what are some of the challenges with doing so?

Different issues will bring different folks together. For example, one issue that I led a working group on was checkoff programs. Checkoff programs are a fund that producers of certain commodities, like dairy or beef or soybeans, will pay into per amount that they produce. That money is supposed to go to broadly promoting the consumption of that product and R&D for that product — we all know the “Got Milk?" campaign and “Beef. It’s What's for Dinner.” One of the issues is that the program has basically been co-opted by industrial animal agriculture, and that money is being used to support their interests at the expense of family farmers. That's a case where cattle ranchers and animal welfare advocates came together to fight a common enemy.

One challenge to collaboration between the farmed animal advocacy and food systems movements has been, rightly or wrongly, the idea that animal advocates prioritize animals at the expense of human interests. Today, the animal advocacy movement is a lot more inclusive and intersectional. There's also some understandable historical distrust there between rural communities and farmers and animal advocates. I think that that's been a difficult gap to bridge. On the other side, there continue to be challenges to collaboration between some food systems groups. Some folks see farmed animals as central to regenerative agriculture and aren't open to considering regenerative models that decenter animal farming. I think it can be off-putting to some animal advocates to see that side of the food systems movement promote beef consumption or cattle ranching as integral to a sustainable food system.

But I think that the animal advocacy movement overall has become much more aware of the importance of a big tent approach, and I think that has helped bridge the gap. There's a place for animals in conversations about the food system, and that doesn't take away the place of any other food systems actors. Animal issues have historically been seen as naive or pie in the sky. We’re really interested in having open conversations that challenge that, recognizing that conversations about the food system have to be about everything in the food system.

What have been some of the historic and current gaps in funding for food systems and farmed animal advocacy, and how do you try to fill that niche?

Historically, the animal advocacy movement has been predominantly very white, leadership has been male-dominated, and the funders have been white and male. That has led to an under-resourcing of groups that are not led by people of those demographics, particularly BIPOC-led groups and community-led groups. That's changing in some really good ways, and we have tried to be part of that change.

In addition, the animal advocacy movement has historically seen a lot of project-based funding. I can understand why a funder would be motivated to ensure that as much of their money goes specifically to their highest concerns, such as chickens in crates or the separation of cows from their babies at birth. However, focusing funding on specific issues may create challenges for nonprofits in covering their basic operating expenses. As a result, Stray Dog Institute has shifted to giving mostly unrestricted, general operating grants. Additionally, we used to give larger grants to fewer organizations. About a year after I came on the team, we decided that we wanted to take a movement-building approach and to spread that support across more organizations in the movement at necessarily smaller grant amounts.

Along with funding in smaller amounts, are you generally funding smaller organizations?

It varies. Sometimes our support may be a drop in the bucket for an organization with a multi-million-dollar budget. Those organizations are doing great work, and we do want to support them. But I find it really meaningful to provide support to smaller organizations who might not have a lot of funder support. A smaller grant can have a larger impact for an organization with a smaller budget. And I think that for those organizations, our support can mean more than the money itself, like having a funder who knows other funders say, “Hey, I'm supporting this organization, I think you might want to consider supporting them, too.”

I've asked you a bunch of questions about your job. I also want to talk a bit about your time at Yale. How do you think your work on the Farm influenced your career path?

My time at the Farm was so foundational to everything that I did in college and beyond. I have always been interested in the intersections between people and animals and the environment. I came into Yale knowing that I wanted to major in environmental studies, but not thinking that I would connect it to the food system so directly. I got pretty burnt out in college because so many of the issues in the food system are just so entrenched and sometimes feel hopeless. It felt hard to be like, ‘I want to focus my career on this.’

Working with the YSFP gave me a space where I could feel optimistic about the food system and working in the food system. The Farm was my happy place at Yale. The Farm was always the place where I went to feel at peace. And the people on the Farm are some of my favorite people in the world. It was very influential in making me feel like this work could be sustainable, and something that brought me joy, and something that's meaningful.

I'm a very hands-on, tactile person. Reading and writing and talking all day gets so exhausting. The appreciation of both hands-on and intellectual food systems work, and the way that those two things combined at the YSFP, felt very energizing.

That's great to hear. I feel like I'm constantly telling people this is the happiest place on campus. Every week I pick a tomato off the vine and I’m like, ‘Ah, life is going to be okay.’ Do you have any favorite memories from your time at the Farm?

Oh, all of them. I remember my sophomore year, when I was a Farm Manager, I worked with another awesome Farm Manager named Adam. We were Sunday workday managers, so there were fewer visitors on the Farm during our workday. There was one time where we raked all the leaves on the Farm into a huge pile and jumped in it. That's just a really happy memory, one of those where you take a photograph in your mind. I also think about the tomatoes in the hoop houses, and seeing the rows and rows of them strung up, and having been part of stringing them up when they were little tiny tomato plants and then seeing them go all the way to the top. Just all of the times walking around the Farm and it feeling like home. Even when there wasn't anyone there, it felt like home.